This is described by Berger as mystification. It’s quite strange the disconnect between pretty obvious reality and the story of the painting which must be neutered. The official page of the Painting on the Hals museum website gives exactly the same opinion. He insists that the painting would have been unacceptable to the Regents if one of them had been portrayed drunk. He cites medical opinion to prove that the Regent’s expression could well be the result of a facial paralysis.

He argues that it was a fashion at the time to wear hats on the side of the head. Regents of the Old Men’s Alm House by Frans Hals ( source) For Slive this interpretation is unthinkable. One Man in this painting looks drunk, hat skewed to side eyes staring unfocussed forward face blotchy. There is no mention of the fact Hals was eighty years old penniless and living off of alms from the very same clients that commissioned the painting. Slive frames the picture in terms of the artists technique, skill and vision. In Regents of the Old Men’s Alm House by Hals. He calls this Mystification.īerger uses the example of the Two Volume study of Frans Hals by Seymour Slive.

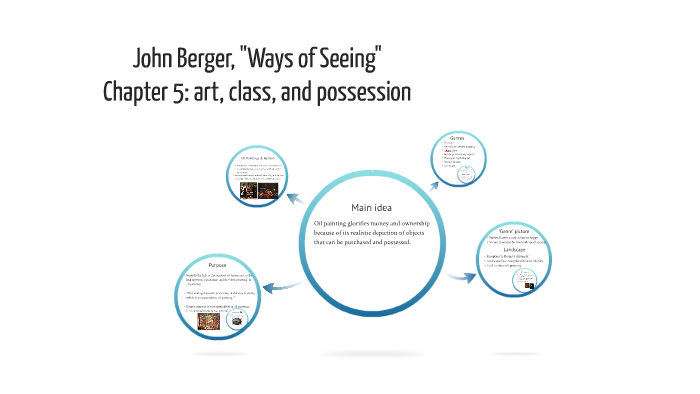

Oil Painting is an example which Berger brings up. This is meant to make people see things in a different way from what is meant or to hide the original meaning. The second main point in Chapter One is that what we see and how we see it is mediated by culture and in some cases that culture has an agenda which may obstruct, and obfuscate the plain meaning of these images. What we see and the way we see it affects us and affects our place within that world. By seeing we establish our place within that world. We can’t help but see the world, and the world presents us with images in return. Nobody has a relationship to images which is uncritical. We never look at just one thing we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves. Seeing is not a neutral thing but always a way of seeing. Both physically and metaphorically as we will see as this book progresses. But it’s not only for looking out it is for placing oneself in relation to what one sees. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak. The Book starts maybe a little more quietly but the first sentence also sets the tone. John Berger narrates in the background as we watch him with knife in hand gouge out a face from a Renaissance painting.

John berger ways of seeing summary chapter 1 series#

The TV series starts with a bang and sets exactly the right tone for the whole. I have missed out the purely visual essays here but they are worthy of consideration and a good reason to pick up the book if only there was a better color version to recommend. Chapter 7 Advertising imagery and modern day image culture.Chapter 5 Ownership in European oil painting.Chapter 3 Women in art and their role as subjects in artwork.Chapter 1 Seeing art, the importance of social and historical context when looking at art, the mystification of art.Ways of Seeing covers four key ideas spread over four essays, there are also three picture essays with no words which provide a kind of space for the essays and provoke themselves themes based on Berger’s arguments in his other essays. Split into seven Chapters or Essays four of which have writing and three which are purely images. The book had a few contributors besides Berger, Stephen Dibb, Sven Blomberg, Chris Fox, and Richard Hollis. The TV series was four 30 minute long episodes meant as a response to Specifically Kenneth Clark’s Civilisation and more generally to traditional forms of Art criticism. Ways of Seeing by John Berger is the book adaptation of the BBC television series made in 1972. Below is a summary and set of book notes with short review. I think anyone interested in Architecture or Design or even mass media should read this book.

It’s key arguments seem ever more urgent in the image hunger age of the internet. Although it deals mostly with painting and photography some of the cultural criticism is I believe relevant to Architecture. It challenged conventional art criticism in a startlingly bold way and changed art criticism forever. Adapted in 1972 from a TV series this book revolutionised visual criticism and remains in print today some fifty years after it was written.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)